How to Outline and Plan a Novel

What I've learned from the first few

In the last year, I've written two novels. The first one went in the trash and the second one, a sci-fi thriller called Husk, is coming out in May. You can pre-order it here.

With Husk done, I’ve shifted my focus to the next two books in the same universe. One is a direct sequel, and the other is a novella where I can go deeper on one of the major events of the universe, the science and philosophy behind it, and a couple of my favorite characters.

One of the big questions that I ran into when I first started trying to write a novel, especially coming from non-fiction writing, was how do I plan and outline this thing?

I tried “discovery writing,” where you start with a couple characters, a world, and a premise, and just go, but that didn’t work very well. I got lost moving in a windy unfocused direction and ultimately scrapped that first attempt, deciding to start over with more of a plan.

But even with that decision made, I still didn't know how to do it. There are tons of options and suggestions out there for how to outline a novel, and I tried basically all of them until I figured out a system I like.

So if you're thinking about trying to write a novel, here's what I’ve learned and the process I’ve developed.

Obviously, I am not an expert at this. But I often find that I learn the most from people who are a few steps ahead of me rather than the people who have been doing something for 20 years.

To give credit where credit is due, it's drawing on lessons from Stephen King, the "The 7-Point Story Structure" by Dan Wells, and “Save the Cat Writes a Novel” by Jessica Brody.

Oh and once again if you haven’t preordered Husk you should go do that!

Step 1: Person-Place-Problem

In "On Writing" by Stephen King, he says that the way he does his discovery writing is he thinks of one or two interesting characters and then a situation that they might be in, and then he just starts writing and sees how they react to the setting.

“The situation comes first. The characters—always flat and unfeatured to begin with—come next. Once these things are fixed in my mind, I begin to narrate.” (On Writing, 164)

Writing and seeing what happens didn't work for me, but I do like the idea of a situation and the characters in it as a starting point. So, the way I think about it is:

A person

A place

A problem

Who is the main character(s)? Where are they? What is the situation that they are in? What is the problem that they are trying to encounter, or the goal that they are chasing after? What is that they want or they need to fix?

For Husk, you get a lot of this from the sales copy for the book:

As a Tech, Isaac maintains the servers housing humanity’s collective consciousness. Tomorrow he turns twenty-five—old enough to transfer into the digital paradise of Meru. Virtual immortality will be his in a world free from the death and disease that plague what’s left of civilization.

But when tragedy strikes, Isaac discovers Meru may not be the paradise he thought. Powerful forces are conspiring to destroy it, and the ones he trusts most have turned against him.

Outcast. Abandoned. Exiled. Isaac must uncover the truth about Meru before it’s too late. And before he suffers a fate he thought was confined to the history books:

Death.

Person: Isaac, a “Tech” whose job it is to keep the servers that preserve digital immortality running.

Place: A post-apocalyptic world where most of humanity has died (in the physical sense at least), and specific to Isaac, one of the locations where these immortality servers are maintained.

Problem: Someone is threatening the digital paradise, and Isaac needs to figure out why and how to stop them.

This is enough to get me started, and then from here I like to start flushing out more of the plot using the “7-Point Plot Structure.”

Step 2: The 7-Point Plot Structure

Once I have the person, place, and problem roughly figured out, the next step is to create the very highest level overarching plan for the story.

Most people are familiar with the simplest story structure: beginning, middle, and end, also known as the three-act structure.

The problem with a simple three-act structure is that it's not very prescriptive: it doesn't tell you that much about how to actually plan a story. You might come up with a beginning, an end, and a couple of things that happen in the middle, but it's not much of a plan, is it?

On the more complicated end, you have structures like Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey. But that one ends up being almost too complicated, and you keep trying to force different things into your story, especially as a first timer.

The other thing I realized is that sometimes, these story structures are as much about explaining stories (or even more about explaining stories) than they are about helping you plan a new one. It can be hard to tell the difference sometimes between whether a structure is more for interpreting something or planning something, and I've found that a lot of story structures don't work that well for the actual planning phase.

After trying a bunch of different strategies, I ended up liking the 7-point plot structure by Dan Wells the best.

The seven points are:

Hook: A compelling introduction to the story's world or characters, capturing the reader's attention.

Plot Turn 1: An inciting incident that brings the protagonist into the adventure, setting the story in motion.

Pinch 1: The stakes are raised with the introduction of the antagonist or major conflict, challenging the protagonist.

Midpoint: A turning point where the protagonist shifts from reacting to acting, often gaining new insights or abilities.

Pinch 2: The major conflict escalates, making the situation worse for the protagonist and raising tension.

Plot Turn 2: The protagonist discovers something crucial that helps them resolve the conflict or defeat the antagonist.

Resolution: The climax where the major conflict is resolved, and the story concludes with the protagonist changed by their experiences.

But despite what you might be thinking, this is not the order that you plan them out. It's actually easiest to start at the ends and to work your way back from there.

Normally, what Dan recommends is you start with the resolution, but we technically already have the hook and a bit of plot turn one from the person-place-problem that we already outlined.

With that in mind, we can go ahead and think about the resolution. Given this person-place-and-problem and the kind of story that you're imagining comes from it, how does this whole thing resolve? You can write that down next.

After that, you can think about the midpoint. What is going to be the shift in the plot middle (not necessarily the exact word count middle of the story) where the protagonist goes from reacting to their environment and the antagonist to being proactive and trying to change the situation.

From there, you can think about Turn 1. What is it that spurs the protagonist to action? What is the inciting incident where their world changes and the meat of the story really begins?

And then what is Turn 2? What is the secret they discover or the big unlock that allows them to finally defeat the antagonist and move into the resolution?

Finally, you can think about Pinch One. What is the event that happens after they've already been called to action that raises the stakes, introduces the antagonist, and eventually spurs them to become more proactive?

After that, you can think about Pinch Two. Once they have decided to start taking action or actually trying to take control of their world, what is it that raises the stakes? What is the really bad thing that happens that leads them to the dark night of the soul where it feels like all hope is lost?

If any of that is unclear, this article has a really good breakdown of how you might think of these aspects in The Hunger Games.

The reason I like the seven-point plot structure is that when you try to plan a novel, you'll often find that it's pretty easy to think of a beginning and ending, but flushing out the middle is really challenging. And if all you have to go off is Act II, you don't really know what to put in there.

So having all these other things - Turn I, Pinch I, Turn II, Pinch II, the Midpoint - gives you a lot more meat to flesh out what's going on between the exciting introduction and the climactic finale so that you're not just wandering around waiting for it to end.

Step 3: World Foundations

This step will probably start to happen while you're in step two, because as you begin flushing out some of the other 7 points of the story, you'll realize that your initial person and place are not really enough to build a whole story around. You're going to need all the other parts of the world that go with it.

Once I have the 7 points, then I like to go back and start flushing out all the other world details that I'm going to need before I plan the story any further.

This is where I'll start making notes on:

Characters: Main, supporting, and tertiary

Settings or set pieces: Areas where significant parts of the story take place.

The technology: Since I'm primarily writing sci-fi, I'm thinking about the tech and how it makes sense and how it can be explained.

The lore or the backstory: Things that aren't going to happen on scene but that are important details to remember to keep consistent.

The sub-plots: Anything separate from the main plot that's going to be important to keep track of. This could be character relationships, it could be minor quests, things that are happening in the background that you want to make sure are tidied up by the end.

Objects, companies, etc: Non-person entities that play some important role in the story.

And anything else that's going to be important or useful to keep track of as I start flushing out the plot.

I like to keep a separate document where I'm listing all this out so that I can stay on top of it. For Husk, this is well over 20,000 words of its own details that aren't in the original book or the novellas (plus a 100,000 word novel, the one I scrapped, providing backstory).

While other people might like to spend tons of time flushing this out first, I have preferred to do it as I'm working through the plot, filling in these details as necessary. That way I'm not just creating unnecessary complexity that I try to justify later by writing tons of world details into the book that don't necessarily need to be there.

Step 4: Scenes

It's a little unromantic, but I find it very helpful to think of a book very analytically.

Conventions for a sci-fi novel, especially from a lesser-known author, would put it at a length of 90,000 to 120,000 words. Or, if you prefer to think of it as pages, that's 300 to 400 pages.

If you're well-known and established, then you can push longer—180,000 words, like Leviathan Wakes; or, if we're digging into the fantasy world, many Brandon Sanderson books are over 400,000 words. But when you're just getting started, you want something on the shorter or more normal length to not completely scare off readers who are trying a new author. So for now, I'm still targeting my books in that 100,000 to 120,000 word range.

120,000 words sounds daunting, so the easiest way for me to break it down is to think of the book as a collection of scenes.

A scene is a loose definition, but it's usually a continuous piece of time where a character wants something and either gets it or doesn't get it.

Morpheus explains the Matrix to Neo and asks if he wants the red pill or blue pill. Bilbo and Gollum compete for the ring with riddles. Darrow cuts down Eo’s body and secretly buries her.

There's a big range to how long scenes can be. I'm reading Neuromancer right now, and some of the scenes are only 100 or 200 words long, and they completely break this convention. At the other end, John Galt's speech in Atlas Shrugged comes to mind, which is itself around 30,000 words, and that's basically one scene.

But as a rough estimate, most scenes in genre fiction are going to be 1,000 to 2,000 words. It's enough time for something to happen, but not so long that you risk losing a reader's attention.

So I estimate that my scenes are going to be 1,500 words long. Therefore, if I want a 120,000 word book, then I need to come up with 80 scenes. And I might come up with 90 to 100 to be safe, assuming I’ll cut some.

Now thankfully, you've already come up with at least seven of these already because each point in the seven point plot structure is going to have at least one if not multiple big scenes that correspond to it. There's going to be an opening scene where you meet the main character or some of the characters and the world. There is going to be an event at the midpoint where the character starts taking action and the pinches and the turns also have very clear corresponding scenes to them as well and the resolution might have at least two scenes that correspond to it. The one where the resolution actually happens and then at least one for the world that comes after. So you already have a bit of a start here.

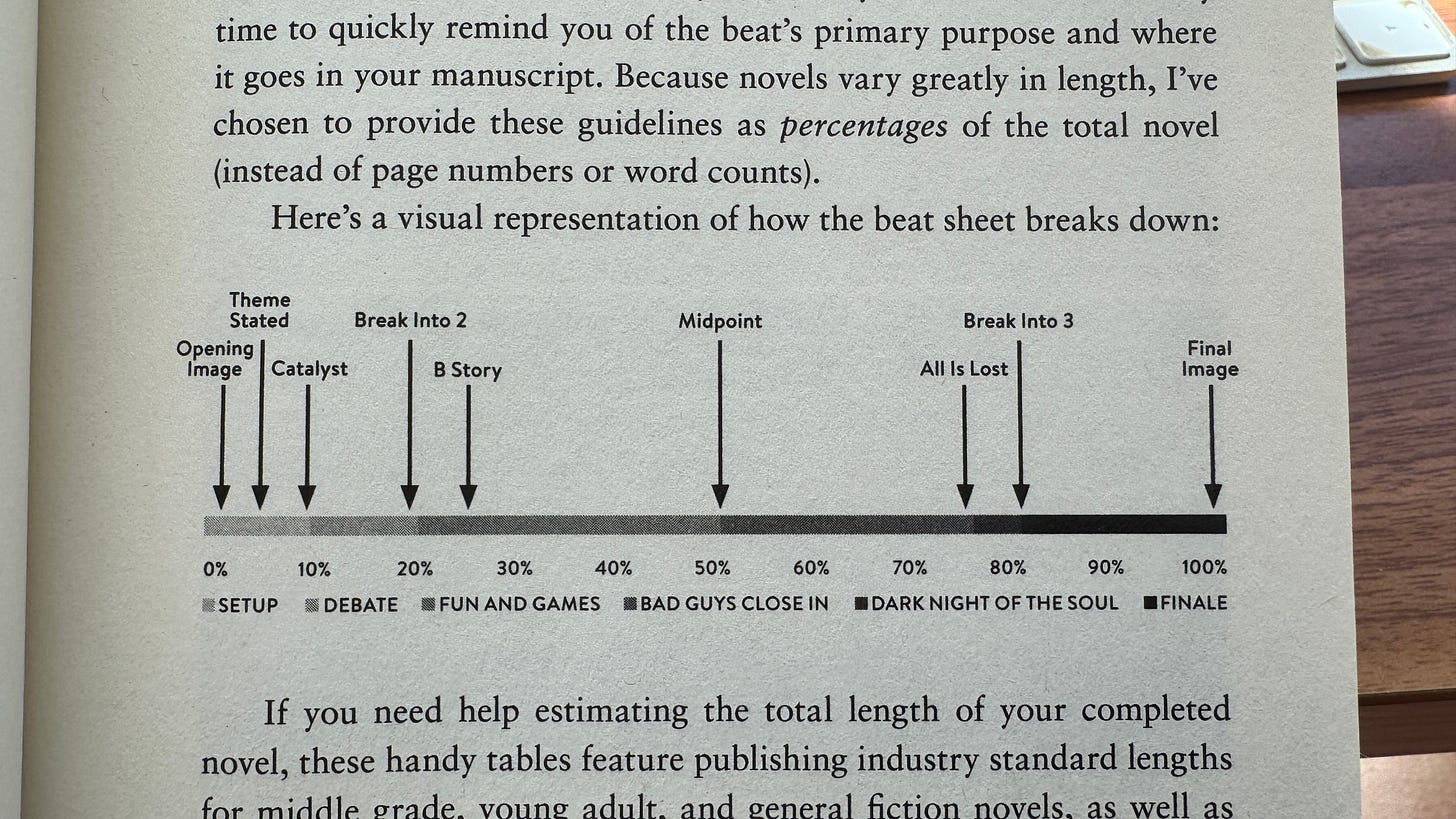

Then you just need to draw the rest of the owl, so to speak, which can be daunting again, and so that's why I kind of like this structure from Save the Cat Writes a Novel.

Translating the 7-point story structure to the Save the Cat structure:

Opening image = Hook

Catalyst = Turn 1

Break into two = Pinch 1

Midpoint

All is lost = Pinch 2

Break into three = Turn 2

Final image = Resolution

From this, we start to get a good idea of how many scenes we want to have in each area. And the math gets very simple here if you plan to have 100 scenes in your book:

First, the hook as the first scene or one of the first scenes.

Then Turn 1 happens roughly around the 10th scene.

So you need to figure out 8 scenes to go between your hook and your inciting incident, your Turn 1.

Then Pinch 1, where things start to get worse, will happen after another 10 scenes or so.

Then you have the long “Fun and games” or “friends and allies” section where you’re building the world, developing the story, trying to solve the problems but it's not working, facing setbacks, which will take about 30 scenes.

Then the midpoint event happens around scene 50 where the protagonist is really spurred into action.

They start taking more direct action for another 25 or so scenes until the Antagonist reaches their peak and it seems like all hope is lost.

A little bit later, about 5 scenes later, they're going to find the key that's going to let them fight back against the antagonist.

And then you have about 20 scenes of going from there to the story being resolved, defeating the antagonist, succeeding, and returning to the original world of the story but forever changed in some capacity.

Now, obviously, you probably won't and shouldn't follow this to a tee, but it starts to give you some ideas for the kinds of things that might be going on and how much should be going on in between all these major parts.

This can also be helpful for revising. You might find after your first draft that you're really lacking in one of these areas. In an early draft of Husk, I had almost nothing in the fun and games section which made the world feel a lot lighter and shallower than it could have been, which is why I went back and focused heavily on improving that part of the book for the second draft.

Step 5: Beats

Now, if you want to get really structured before you actually start writing to completely make sure that you don't run into any degree of writer's block, the last step that you can do once you have your scenes is to actually list out the beats that are going to happen in each scene.

If a scene is a character wanting something, either getting it or not getting it, there are probably going to be a few different things that happen within that scene.

Maybe they go somewhere, they have a conversation with this person, this surprising thing happens, there's some kind of conflict, there's going to be multiple steps within that scene that lead to that scene's resolution.

The benefit of doing this is that if you plan your novel down to this level, then once you actually start writing it, you're basically never going to have to stop. You're never going to get stuck. You're never going to have writer's block. You will know exactly what is happening next every single step of the way.

To be honest, I don't do this step that religiously because I feel like it takes some of the fun out of the actual writing where I like to discover bits as I'm going. But you might find it's very useful if you're worried about getting stuck along the way.

Step 6: Write!

At some point, probably in step 4, you're going to hit a point where you feel like, "This is good enough for me to get started." If that's the case, then I think you just go ahead and get going.

You definitely want to do enough planning that you don't get stuck and that you have a good idea of where you're going, but you also don't want to do so much planning that you never start writing.

I might not even list out all 100 scenes because I like to find some of them as I'm going, and I want to leave some space for that and not spend too much time on the planning process.

And remember, this isn't something where you do it once and then never touch it again. I'll typically keep refining my outline and make tiny tweaks to it every day while I'm writing as I'm figuring out more about what the story is. So, again, you want to be thoughtful in planning, but also not overdo it.

Anyway, this is what’s working for me right now. I hope it helps you too if you decide to try writing a novel, and don’t forget to preorder Husk!

Well done! Very useful guideposts. Thanks for putting these out there for all us starving, soon to be well-fed writers.

I bookmarked this post to return to after finishing my novel research. Extremely helpful! I also found it helpful to put the seven-point structure into ChatGPT and ask it to break down novels similar to mine into that structure. This really helped me visualize it -- I read these books as part of the research, but this helped put it together. https://chatgpt.com/share/6806c7ee-c340-800d-8c53-6557d252b0ec