How to Be (Reasonably) Hard on Yourself

The mantra

I’m never completely satisfied with a piece of writing I’ve published. I can always find some piece of it to criticize, or imagine some other writer who could have done it better.

Being on a weekly schedule with this blog was an unintentional form of self-preservation. When I knew I had to publish something, it gave me permission to publish something that was “good enough.”

Sometimes good enough was surprisingly good. Many times it wasn’t. But often my feelings about the piece had little to do with its reception. Despite writing online for over a decade now, I’m still rather bad at predicting what will hit and what won’t.

The other self-preservative boon of publishing online was the availability of instant praise. When you get to a certain popularity you can find someone who likes every single thing that you publish. You get some immediate pushback against your self-criticism.

But when I started working on Crypto Confidential, I quickly ran into trouble. All of my same self-critical voices were there, but there was no public praise to push back against it. And while I had a deadline from the publisher, it was a year away, with what felt like infinite time to stew in between.

The solution was clearly not to buy into some self-love-illusion where I try to convince myself that the work is fantastic and the real problem is that I’m not nice to myself. If you’re completely uncritical of your work, you’ll get stuck in a plateau of mediocrity. It might feel good being there, but assuming you’re reasonably ambitious you’ll wake up in a few years and realize you were treading water, never improving your craft because you were too afraid to be honest with yourself.

But the opposite end isn’t great either. Creative work shouldn’t feel like The Bear or Whiplash. If you fully embrace the obsessively self-critical mindset it can have disastrous consequences, regardless of your skill level.

It took a decent bit of grappling, but I landed on an embarrassingly simple mantra, backed by a deeper understanding of how good your work can actually be over time.

First, part one and two of the mantra. I’ll share part 3 in a minute.

It’s Good.

It Can be Better.

It’s a little trite, but try it out next time you’re feeling hard on yourself. If you’ve gotten some way into a creative project, the odds are it’s not terrible. It’s probably not where you want it to be or where you’ve imagined it can be, but it’s hopefully at least decent. And it can be better.

It feels like those two ideas should be at odds. If you accept that it’s good, then you will lose the motivation to make it better. But if you understand how the quality of your work evolves throughout projects and time, you’ll see that’s not the case.

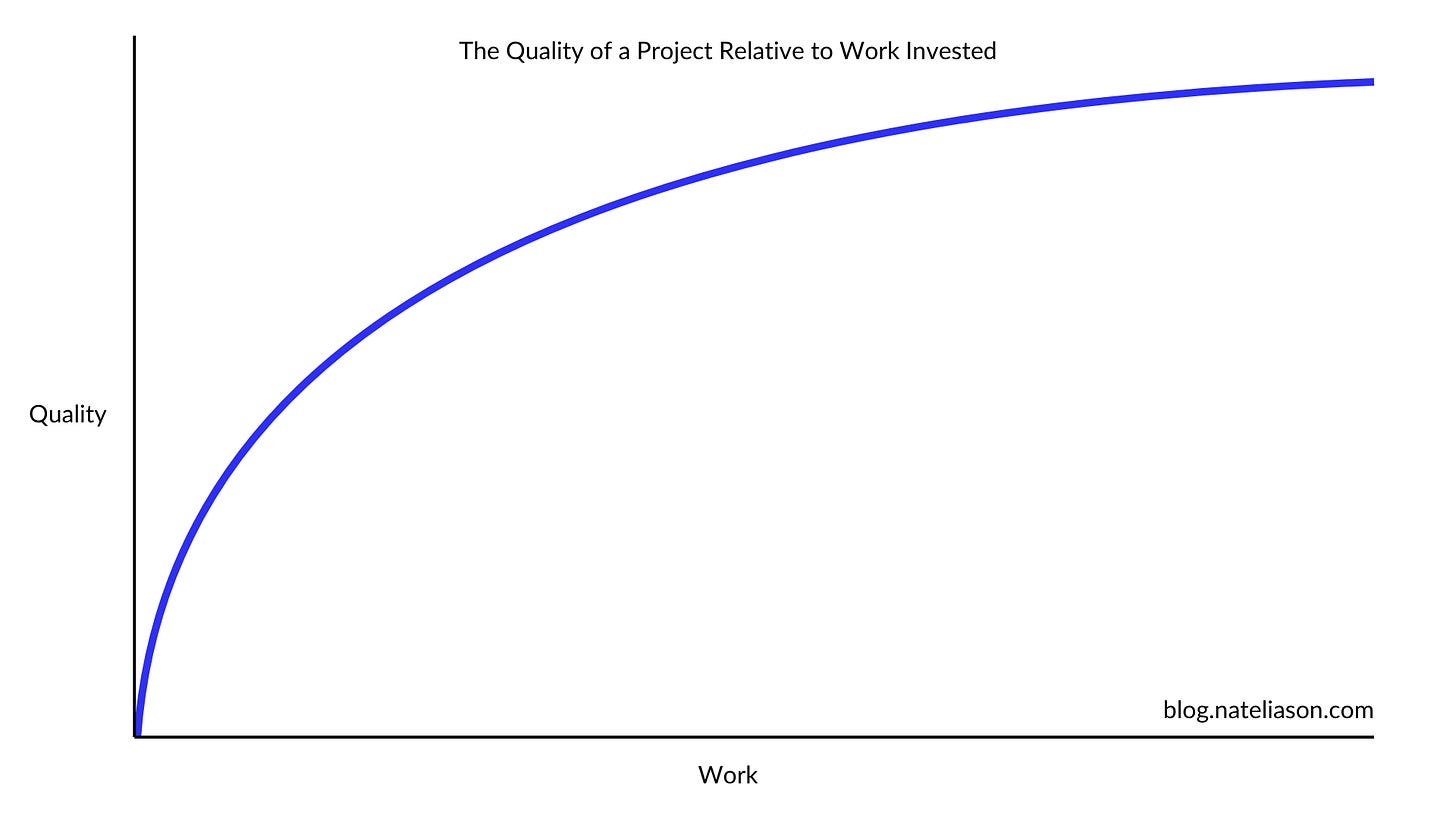

Every project exists on a quality curve that looks something like this:

Simply by starting and making a little bit of headway on a project, you’ve made some progress towards creating the work you’ve imagined in your head.

And in the beginning, that progress is fast. It’s why some people (definitely not me) will continually start new things only to abandon them just as quickly. It feels good to be on the left side of the curve when a little bit of work goes a long way. But as you keep working, each additional unit of work makes a smaller incremental move upwards in terms of quality.

So if you get past that initial jump and keep working on it, it’s natural to start to feel frustrated and more self critical. You’re bashing your head against the wall trying to make it better and it’s barely making any difference. But that’s okay! That’s just how it works. The more you chisel, the less marble there is to chisel.

Which is why we need part three of the mantra:

It’s Good

It Can be Better

Eventually it Will Be Good Enough

The thing about the work and quality curve is that it’s infinite. It never touches 100% because you can never be 100% satisfied with your work. And your work will, sadly, never be 100% as good as it could be.

So you can’t aim for 100%. You have to pick some lower number where you’re willing to send the work out the door.

There’s no right answer for where your “good enough” number should be. Andy Weir, author of The Martian, takes around 4 years between his sci-fi novels. He has a much higher Good Enough number than someone who’s churning out popcorn Kindle books every 2-3 months.

But you can’t set the number too high. Eventually the work just has to be released, because any incremental effort on it is not going to make the work much better, and it’s not going to teach you very much.

Because here’s the other thing about the work quality curve: it also applies to your lifetime of projects, with each project potentially moving you further up the curve.

The Red Rising series is a wonderful example of this phenomenon. The first book, Red Rising, is excellent. I highly recommend it. But book 3, Morning Star, is much better. And book 6, Light Bringer, is even better.

I don’t think it would have been possible, though, for Pierce Brown to make Red Rising as good as Light Bringer. He didn’t know how yet. He only got better, and got closer to what I imagine was his quality goal all along, by finding the right “Good Enough” point for each book, sending it off, and starting work on the next one.

This is why it’s generally a waste to go after big goals like “run a marathon” or “publish a book” just to check them off your bucket list. You’ll exert a huge amount of effort only to produce the worst version of something that you’re capable of. It might still be good! But you only get really close to your ideal of good by getting more reps in.

So I suppose there’s a part 4 to the mantra:

It’s Good

It Can Be Better

Eventually it Will Be Good Enough

Next Time Will Be Even Better

Be reasonably hard on yourself to make sure you’re always moving up that curve, but don’t expect yourself to jump all the way to 100 on the first go. That might not even happen by the time you die.

That’s okay though. You can still enjoy getting better along the way. And your work will probably be better than you think it is.

Thanks for reading, if you enjoyed this, please subscribe to make sure you don’t miss the next essay!

Good enough post, Nat. Thanks. On the quality curve, my experience is that sometimes it's more like kneading dough—too much work and it gets worse. So the curve dips. But I see your point that there's a meta curve composed of all these curves and to keep pumping out more and more delicious pastries.

Wow Nat, great post! Given your popularity level, I like every single thing that you publish!