Insecurity Screams, Confidence Whispers

“What am I trying to convince myself of?”

Last week’s Nat’s Notes was about Straw Dogs by John Gray, a book that challenges the philosophy of Humanism and explores topics like why progress is a myth, science is a form of faith, and we’re secretly terrified we’re useless. Check it out on Spotify, YouTube, Apple, or wherever you listen to podcasts!

When I tell people I’m working on a crypto book, I often get some form of the question:

“So, you think crypto is coming back?” or “Isn’t crypto dead?”

There were no Super Bowl ads this year. No celebrities shilling NFT projects. No more laser eyes on Twitter. And most of the people who got into it in 2021 to 2022 are broke or bag holders or writing threads about ChatGPT. Crypto certainly feels dead in most places you look.

The usage metrics tell a different story, though. There are arguably more people using Bitcoin, Ethereum, and the various new networks sprouting up today than at the mania's peak.

But where is all the noise? I think it’s actually well-demonstrated by Do Kwon, the founder of the Terra Luna blockchain that blew up over the course of a week and erased about $70 billion.

At the peak of the crypto mania in 2021 and 2022, this wasn’t unusual for Do to tweet. He was a raging, belligerent asshole on social media.

But despite his behavior (maybe partially because?) he had a cult-like following. True believers had #LUNA in their Twitter bios and put little moon emojis beside their names. If you tried to call Luna the unsustainable Ponzi scheme it was, the faithful would flood your replies, berating you for your idiocy.

To some, I imagine this looked like the mark of a rapid, engaged community. But in retrospect, it reeks of something else:

Insecurity.

Anyone who looked at Luna long enough knew there was something unusually unsustainable about their business model. I even wrote about it a few months before they blew up. But if you were invested in it during that runup, you were getting an insane return.

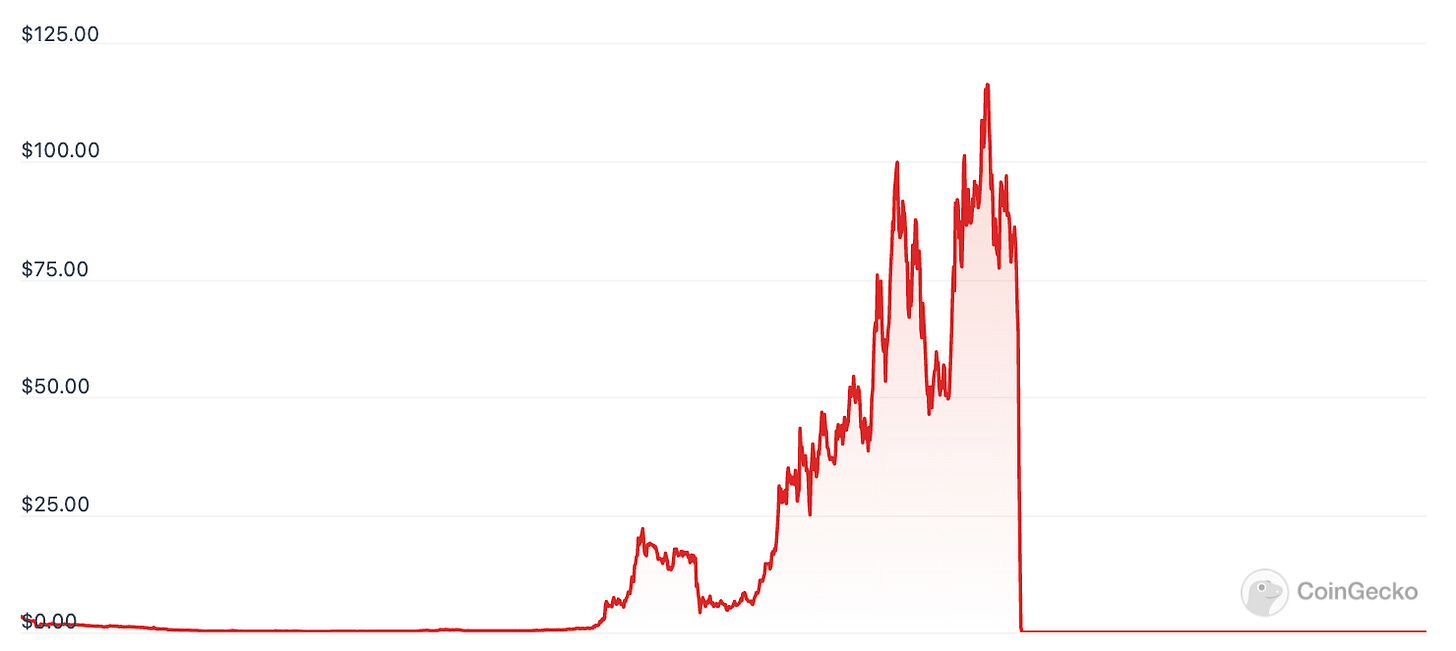

Not only did the LUNA token go from $5 to $115 in a year, but you could earn a fixed 20% APR on their US Dollar pegged stablecoin. There was almost nothing else like it. And then…

Naturally, the longer you rode that wave and the more money you made, the more you had to realize on some subconscious level that this couldn’t go on forever. Something had to break.

But acknowledging a splinter of doubt like that is rather uncomfortable. The cognitive dissonance is too strong. So most people react to self-doubt by trying to convince themselves that their earlier beliefs are fine. It’s their doubt that’s wrong.

And the best way to affirm their pre-existing beliefs is by getting other people to adopt those beliefs. And the closer they get to the cliff, and the more that splinter grows, the more they will have to proselytize their belief to counteract the growing insecurity.

Which leads to two interesting consequences:

1: The more rabidly a community proselytizes, the closer they probably are to being proven wrong.

2: The more FOMO you have from a proselytizing community, the less you should probably listen to them.

The best time to buy into LUNA or any of the other manic crypto cults of the last cycle was before anyone was basing their identity around them, and the time to get out was once people became religious about them.

But, of course, most people did the opposite. They misinterpreted manic insecurity as validation and followed the herd at the point of peak risk.1

Crypto is a good lens to see how the intensity of belief is an inverse signal over time, but we can apply the same idea to the intensity of beliefs outside of it.

The more aggressively someone tries to convince you of something, the more insecure they are in their belief.

But somewhat paradoxically, this insecurity is completely invisible to them. They will feel extremely confident about their most insecure beliefs.

The paradox is a natural consequence of cronyism and intersubjective beliefs. The more your beliefs rely on other people also believing them, the more worried you will be about their fundamental legitimacy, and the more aggressively you will feel the need to convince others of them.

And the more cognitive dissonance and mental splinters you have around those beliefs, the more you will feel the need to double down to re-convince yourself of their validity.

You can observe people do this in real-time if you pay close attention. Someone will start explaining something, and if you’re attuned to it, you will notice they’re just trying to convince themselves.

It’s why the more extreme beliefs often have the most intense zealots. Extreme beliefs are, almost by definition, often the ones with the least evidence to support them. So they require the most forceful intersubjective validation. Vegan and carnivore diets need much more social validation than, well, I don’t have a name for “eating normally” because it’s not something people tie their identity to.2

When you observe other people, it’s probably a good heuristic to assume that the more emphatically they try to convince you of something, the less you should believe it.3 People confident in their beliefs don’t care if you agree with them.

And when you notice yourself trying to convince someone of your beliefs, it’s an opportunity to look at yourself and wonder why you care so much if they agree with you. Does some part of you quietly doubt what you’re espousing?

Crypto hasn’t gone anywhere, just the zealots. The people who have confidence in the tech and the long-term vision are still quietly working or watching.

I doubt you make your religious, nutritional, and political decisions based on who’s screaming the loudest on social media.

You probably shouldn’t make your financial decisions that way, either.

Including me.

Perhaps if you can explain your beliefs with a name, you haven’t thought about them very hard.

Yes, yes, obviously, there are exceptions, but it’s not a bad heuristic.

2. Omnivore

So good. Always a red flag when people base their identities around a singular belief (especially when that thing is new, trendy, and has a financial incentive)...